You may have noticed this news item about a class action lawsuit against AT&T Mobility and Radio Shack.

So, how did we get to the place where Billie Parks, an honest subscriber, gets surprised with a $5000 bill?

Fundamentally, the problem is that mobile broadband has deployed onto a scarce resource, namely wireless spectrum. So, YES, 3G and 4G technologies are capable of multi-megabit download speeds, and, NO, they cannot provide those speeds to all of the subscribers in a sector at the same time.

The solution to this problem, in AT&T’s view, is to charge an additional fee for each Megabyte of data consumed above 5 Gigabytes during the month.

Huh??? How does that solve the problem???

I guess in AT&T Mobility’s view the answer is obvious: the economic penalty for consuming more than 5GB is so steep that Billie Parks will willingly stop consuming data when her limit is reached. Then, with Ms Parks offline, or in the back of the bus, so to speak, there will be room on the channel for other subscribers to consume their share of those multi-megabit download speeds.

That logic is flawed and has appeared to work for a few years, but only because 5GB is plenty for the road warriors using laptops that need ubiquitous access to email, and because the devices that consumers use are not well suited to consuming lots of entertainment. Why would anyone want to pull 5GB of video down to a cell phone???? They wouldn’t, of course.

But Billie is a consumer, interested in entertainment, and using a laptop.

AT&T Mobility extended the subsidy model beyond cell phones to include ultraportable laptops with built-in HSPA, and the result is a very attractively priced computer.

If you are one of the many computer users that have grown to love watching TV shows via Hulu, then you can imagine why Billie Parks ran over her limit. The logic goes like this:

Billie: “I have a trusty old computer at home and I watch my favorite Hulu TV shows on it. AT&T and Radio Shack jointly offered to sell me a very attractive new laptop for $100. How can I pass that up? Now I can watch my Hulu shows anywhere!”

AT&T’s response: “Yup, you sure can.” (And in fine print): “Oh, but be sure to stop watching when you get to 5 GB.“

And then Billie is supposed to say: “OK, I’ll check my account on AT&T’s website frequently and the 5GB limit will probably be reached at a time that is convenient for me.”

Yeah, right.

The real solution to the problem lies not with economic penalties, but with the integration of billing systems and QOS controls. I’ve mentioned wireless broadband QOS in previous posts (here, here) and I’ll keep bringing it up because it is a topic I’m passionate about.

Billie Parks was offered one choice of service:

- Best Effort Hi Rate Pkt Data (HRPD), with a 5GB cap, for $60 per month

- Good for email, browsing and file downloads

- Also good for Hulu if the sector is lightly loaded

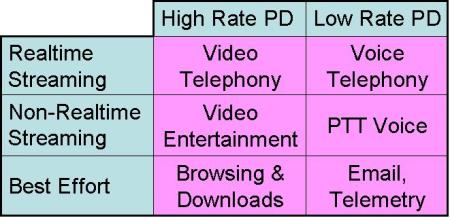

But mobile packet data service needs should be segmented into multiple categories:

According to the segmentation in that table, here are the service options she could be offered instead:

- Best Effort Low Rate Pkt Data (LRPD), no cap, $10 per month

- Good for email, Machine-to-Machine telemetry, GIS tracking, instant messaging

- Streaming LRPD, no cap, $15 per month

- Good for PTT voice but not full-duplex voice

- Realtime Streaming LRPD, no cap, sold in minute usage bundles

- Good for voice telephony

- Best Effort HRPD, no cap, $40 per month

- Good for browsing and file downloads, but you may not be satisfied with the result if you try streaming data – depends on sector loading

- Streaming HRPD, no cap, $60 per month

- Good for video entertainment like Hulu

- Realtime Streaming HRPD, no cap, sold in minute usage bundles

- Good for video telephony (a future service)

(My price suggestions are just that, and the market will ultimately determine pricing.)

Note that I proposed no caps on any service. When QOS controls are used it’s not necessary to also use caps and penalties to motivate certain usage patterns. QOS will allocate the available bandwidth in the sector according to the service that the subscriber is authorized to receive. And if too many subscribers are authorized for the available bandwidth, then the next subscriber will be denied service, or offered a lower-grade of service. In this manner, when a sector approaches its capacity limits, users with “best effort” subscriptions will find their connection to be slow and intermittent, while users with “streaming” subscriptions will continue to receive satisfactory service. Wa-la! People get what they paid for, with no caps and no billing surprises.

My friend Dan commented about Billie Parks’ lawsuit at lunch yesterday, saying “she’s the Rosa Parks of wireless.” Hopefully her stand against the archaic usage caps will accelerate the deployment of QOS based service offerings on the part of the mobile operators. I’m definitely pulling for her to win this one.

Posted by Bill Jenkins

Posted by Bill Jenkins